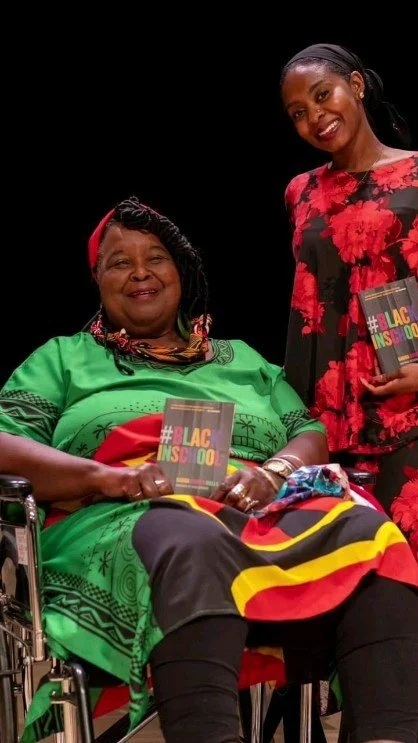

HABIBA DIALLO

AUTHOR. SPEAKER. END FISTULA ADVOCATE.

Short Bio

Habiba Diallo is the author of #BLACKINSCHOOL (University of Regina Press). She is the inaugural winner of the Senator Don Oliver Black Voices Prize for literary talent. She was a finalist in the 2020 Bristol Short Story Prize, the 2019 Writers' Union of Canada Short Prose Competition, and the 2018 London Book Fair Pitch Competition. Her Netflix-sponsored debut short film, Black In School, was inspired by her book and made the official selection of film festivals across Canada. She is an activist in support of women's maternal health. The federal government of Canada recognized Habiba as an outstanding woman in 2019. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in African Studies from the University of London (SOAS) and a postgraduate certificate in Public Health.

FOLLOW ME ON INSTAGRAM

Longer Bio

My name is Habiba Diallo. I am an author and an activist for the eradication of obstetric fistula. I am of mixed West African (Guinea, Conakry) and Caribbean (Jamaican) heritage. My culture has shaped who I am and my experiences in the world. My late father, rest his soul, passed away during my first year of high school. He spent his early years in Liberia—where he fondly called home—before moving to Kuwait as an adolescent. I have been fortunate to live and experience both my parents’ cultures and visit my ancestral homelands. The rich settings, language, colour and social behaviours of these places and their people have very much influenced my writing.

During the summer of 2008, I was inspired by my own culture to do research on West African ethnic groups. I came across an article about a young Tuareg girl from Niger named Anafghat Ayouba. After four days of labour, Anafghat gave birth to a still born baby boy and developed a fistula between her bladder and vagina. Anafghat’s story touched me in so many ways. At the time of reading the article, I was about the same age as she was when she developed fistula. I felt bound to her by a cultural and a human thread. It was in reading another article about Anafghat that I learned of her death. It read, in 2007 “[Anafghat] died suddenly from complications of an infection on May 25.” I remember crying upon reading this. In one report she was alive, in the next, she was dead. My shock at her death thus propelled me into an extensive study of obstetric fistula, which would eventually begin my journey as an advocate for bringing an end to this tragic condition.

I took my passion for fistula with me to school. That fall, I entered grade 7 and whenever I was given any liberty with regards to completing classroom assignments, I always found ways to creatively integrate fistula into them. By the end of middle school, I had written two short stories both on the topic of fistula. This trend continued on into high school where I wrote an article about Anafghat’s experience with fistula for my school newspaper and would discuss the affliction with my peers. By grade 10, I had read one of my short stories on fistula at Toronto’s Word on the Street, Canada’s largest outdoor literary festival, and had given a TEDx Talk about the affliction. In the spring of 2012, I launched my organization, WHOI, the Women’s Health Organization International, to bring fistula to the attention of the Canadian public and to address certain medical concerns of African-descended women living in Canada. The founding of WHOI led to several opportunities for me to educate people about fistula in communities across Canada.

My non-profit is a partner to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Campaign to End Fistula and, in 2019, the Federal Government of Canada recognized me as an outstanding Canadian woman.

I have also been able to learn more about the women affected by fistula through my travels to hospitals and clinics in Ethiopia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Senegal, and Ghana. I have raised funds for women living with obstetric fistula in Ghana and Ethiopia. I have also developed training programs, and organized conferences and awareness events for Black women’s health in Canada. Given that fistula does not afflict women living the Western world, people often struggle to relate to the plight of fistula patients. I realized it was necessary for me to start FEP, the Fistula and Empowerment Program to bridge the gap between women who suffer from fistula in Africa and women of African-descent living in Canada who experience barriers to accessing quality health services.

I started this blog to document the work I have been doing on fistula for the past 17 years since that summer in 2008 when Anafghat entered my life. Together, we can put an end to fistula.